Building Performance Simulation for Decarbonization and Climate Resilience in Tropical Vietnamese Buildings: A Practical Guide

Overview

Vietnam’s tropical climate presents unique challenges and opportunities for building design. High temperatures, humidity, intense solar radiation, and increasing frequency of extreme weather events due to climate change demand sophisticated approaches to ensure buildings are energy-efficient, comfortable, and resilient. Building Performance Simulation (BPS) is a powerful tool that allows architects, engineers, and sustainability consultants to predict the energy consumption, thermal comfort, and environmental performance of buildings under various conditions. This guide provides practical steps for leveraging BPS specifically for decarbonization and climate resilience in the Vietnamese context, helping practitioners navigate local requirements and maximize building performance in a challenging climate.

By accurately modeling energy flows (heating, cooling, ventilation, lighting, plug loads), moisture dynamics, and the impact of passive design strategies, BPS enables informed decision-making from early design stages through renovation. For tropical Vietnam, this is crucial for minimizing reliance on energy-intensive cooling, promoting natural ventilation, managing humidity, and designing for increased heat, humidity, and potential flood/wind events predicted by climate models 1, 2, 3. Ultimately, BPS supports the transition to a low-carbon built environment and enhances the longevity and functionality of buildings in the face of climate change. Promoting net-zero carbon in the Vietnamese construction sector is increasingly important, and BPS is a key enabler for this goal 4.

Step-by-step Procedures

Define Project Goals and Scope:

- Clearly articulate what the simulation should achieve. Is the primary goal energy code compliance (e.g., QCVN 095)? Maximizing energy savings? Achieving a specific green building rating (e.g., LOTUS[^6])? Enhancing thermal comfort? Assessing resilience to future heatwaves or power outages? Decarbonization involves reducing both operational and embodied carbon; BPS primarily focuses on operational energy, though lifecycle assessment tools can integrate simulation results.

- Define the level of detail required. Is it a conceptual massing study or a detailed analysis of a specific HVAC system?

- Establish performance targets (e.g., % energy reduction compared to baseline, predicted energy use intensity - EUI, hours exceeding comfort limits).

Collect Input Data:

- Climate Data: Obtain accurate weather files representative of the building’s specific location in Vietnam. Typical Meteorological Year (TMY) files are standard for energy simulation [^7]. For climate resilience studies, source or construct future climate files reflecting projected temperature increases, humidity changes, and extreme events based on regional climate models and IPCC scenarios 2, 3. ASHRAE provides guidance on climate data and its use in simulation [^7].

- Building Geometry and Properties: Accurate architectural drawings are essential. Model the building’s form, orientation, shading devices (louvers, balconies), window-to-wall ratios, and internal layout. Define material properties (thermal conductivity, density, specific heat, absorptivity, emissivity) for walls, roofs, floors, and glazing systems. Pay close attention to thermal bridges, especially in concrete structures common in Vietnam.

- Internal Loads: Specify realistic occupancy schedules and densities, lighting power densities, and equipment power densities based on building type and expected use 5, [^6].

- HVAC Systems: Define the type, efficiency (COP, EER, SEER), control strategies, and zoning of HVAC systems. Modeling natural ventilation potential, ceiling fans, and dehumidification strategies is critical for tropical climates.

- Operating Schedules: Detail when the building is occupied, when systems operate, and lighting schedules.

Build the Simulation Model:

- Use appropriate BPS software (e.g., EnergyPlus via interfaces like OpenStudio, DesignBuilder; IESVE; TRNSYS; eQUEST). Choose software capable of accurately modeling thermal mass, solar heat gain, natural ventilation, and humidity effects.

- Construct the 3D geometry. Ensure correct zone definitions aligned with HVAC zoning and usage patterns.

- Assign material properties and constructions to all surfaces. Double-check U-values, Solar Heat Gain Coefficients (SHGC), and visible transmittance for windows. For tropical climates, minimizing solar gain through appropriate SHGC and external shading is paramount.

- Input internal loads and operating schedules.

- Model HVAC systems, including controls like thermostats, economizers (if applicable), and potentially dehumidification setpoints. For natural ventilation, define operable windows and ventilation control strategies based on temperature or CO2.

Simulate Baseline and Design Variations:

- Run a simulation for a baseline case. This might be a code-minimum building (e.g., compliant with QCVN 095), a typical practice building, or the existing condition for a renovation project.

- Create and simulate variations incorporating proposed energy efficiency and resilience measures. Examples for tropical Vietnam include:

- Improved wall and roof insulation (though less critical than solar control in hot climates, it still helps).

- High-performance windows (low SHGC, appropriate U-value).

- Optimized shading devices (orientation, depth).

- Enhanced natural ventilation strategies (cross-ventilation, stack effect) combined with ceiling fans.

- High-efficiency HVAC systems.

- Passive cooling techniques (thermal mass with night purge, evaporative cooling - consider humidity).

- Optimized lighting design and controls.

- Roof gardens or cool roofs to reduce solar absorption.

- For resilience studies, simulate performance under future climate files or during hypothetical extreme events (e.g., extended power outage combined with a heatwave).

Analyze Results:

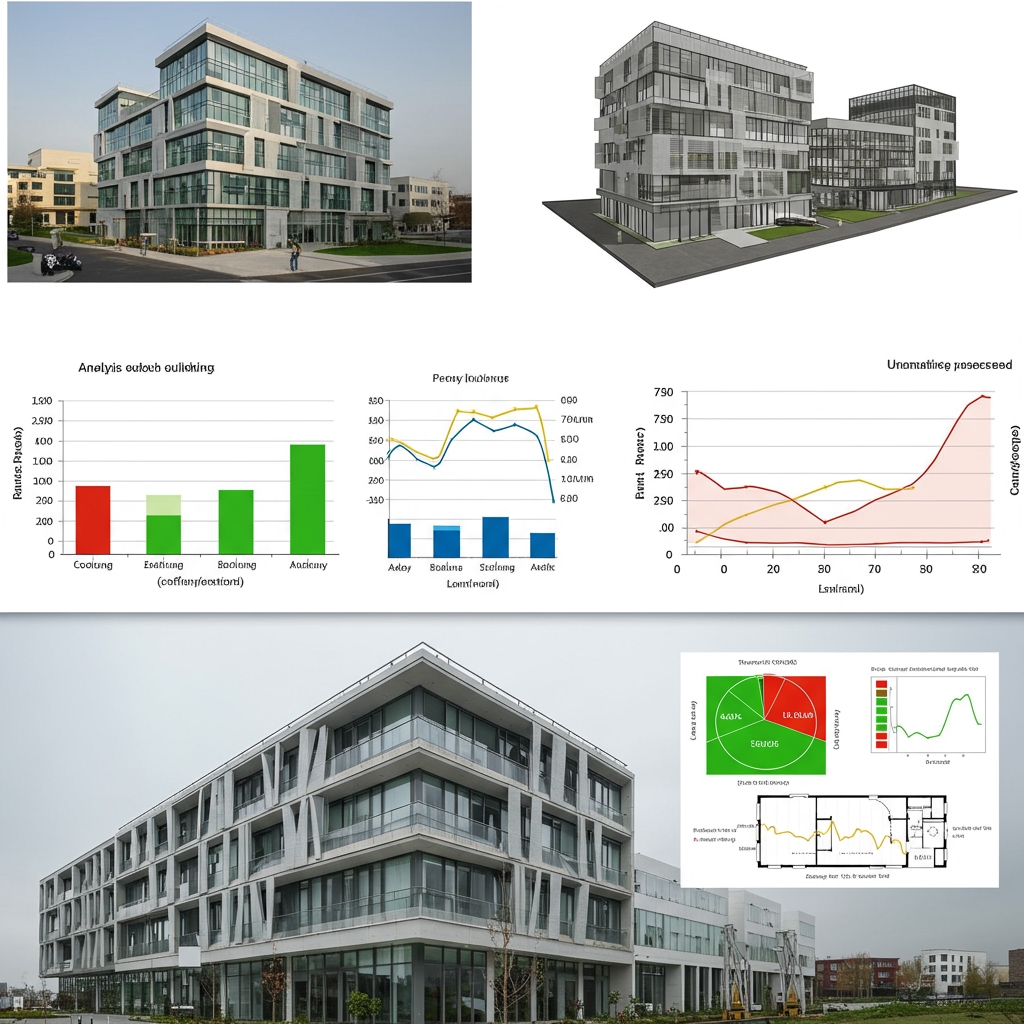

- Analyze total energy consumption and breakdown by end-use (cooling, lighting, fans, equipment). This directly relates to decarbonization efforts by reducing operational carbon.

- Evaluate peak demand, which impacts grid stability and potential for demand charges.

- Assess thermal comfort using relevant metrics. ASHRAE Standard 55[^8] is widely used, but adaptive comfort models (like the ASHRAE 55 adaptive comfort boundaries or the EN 15251/EN 16798 adaptive comfort standard) are often more appropriate for naturally ventilated or mixed-mode buildings in tropical climates where occupants adapt to warmer conditions [^9]. Analyze metrics like Predicted Mean Vote (PMV), Predicted Percent Dissatisfied (PPD), and compliance with adaptive comfort zones.

- For climate resilience, analyze how thermal comfort and indoor temperatures are maintained during extreme heat events or power outages, or how energy consumption changes under future climate scenarios. Look at metrics like hours above a critical temperature or peak indoor temperatures.

- Compare the performance of design variations against the baseline. Quantify energy savings, cost savings (using local energy tariffs), reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, and improvements in comfort or resilience.

- Report Findings and Recommendations:

- Present results clearly, using charts and graphs to illustrate energy breakdown, savings, and comfort metrics.

- Explain the impact of each analyzed measure.

- Provide actionable recommendations for the design team based on the simulation results. Prioritize measures based on effectiveness, cost-benefit, and alignment with project goals.

- Document all assumptions, input data sources, simulation software used, and model details to ensure transparency and reproducibility.

Best Practices

- Prioritize Passive Design: In tropical climates, passive strategies like orientation, shading, natural ventilation, and thermal mass (used strategically) are often the most effective and cost-efficient ways to reduce energy demand and improve comfort [^9]. Simulate these thoroughly before optimizing active systems. Improving building thermal performance through an envelope-based approach is particularly effective 5.

- Use Appropriate Weather Data: Ensure the weather file accurately represents the local climate, including temperature, humidity (dew point), solar radiation, and wind speed/direction. For resilience, exploring multiple future climate scenarios is recommended.

- Model Shading Accurately: External shading is critical. Model louvers, balconies, fins, and surrounding buildings precisely. Internal shading (blinds, curtains) is less effective but should also be considered if part of the operational strategy.

- Account for Humidity: Tropical climates have high humidity, significantly impacting thermal comfort and cooling energy (latent load). Ensure your simulation tool handles latent heat properly and consider dehumidification strategies. Adaptive comfort models can account for humidity effects on perceived comfort.

- Validate Your Model (if possible): For existing buildings undergoing renovation, calibrate the model against actual energy bills and temperature measurements to increase confidence in the simulation results.

- Perform Sensitivity Analysis: Investigate how changes in key parameters (e.g., window SHGC, insulation levels, occupancy schedules) affect overall performance. This helps identify the most impactful design decisions.

- Consider Occupant Behavior: Building performance is heavily influenced by how occupants use the space and systems (e.g., opening windows, adjusting thermostats). While hard to predict precisely, consider different scenarios or use realistic behavioral models if available.

- Integrate with Design Process: BPS is most effective when used iteratively throughout the design process, not just as a post-design check for compliance.

Vietnamese Implementation Considerations

- Local Codes and Standards: Be familiar with QCVN 09/BXD 5, the Vietnamese national technical regulation on energy efficiency in buildings. BPS is an accepted method for demonstrating compliance, particularly for prescriptive and performance-based approaches. The LOTUS Green Building Rating System [^6] also heavily relies on BPS for awarding energy credits.

- Available Technologies and Materials: Understand the typical construction materials and systems available locally. Specify materials and technologies that are accessible and maintainable in Vietnam.

- Climate Change Vulnerability: Vietnam is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts, including rising sea levels, increased frequency of heatwaves, and changes in precipitation patterns 2, 3. Incorporate future climate data analysis into your simulations, especially for long-lifespan buildings. Consider resilience strategies beyond just energy efficiency, such as designing for passive survivability during power outages in extreme heat.

- Data Availability: While TMY files are available, detailed local climate data for specific microclimates or future projections might be limited and require careful sourcing or downscaling. Information on the actual performance of local building materials and systems might also need field investigation or reference to regional studies 5.

- Capacity Building: There is a growing need for skilled BPS practitioners in Vietnam 1. Investing in training and professional development is crucial for expanding the use and quality of simulation studies.

Compliance Requirements

BPS is primarily used in Vietnam for demonstrating compliance with the performance path of QCVN 09/BXD 5. This requires comparing the simulated energy performance of the proposed design against a baseline building model that meets the minimum prescriptive requirements of the code. The simulation must follow specific modeling rules and reporting formats defined within the code or accompanying guidelines.

For LOTUS certification [^6], BPS is essential for achieving credits in the Energy category, specifically for optimizing energy performance. The credit requirements specify baseline definitions, simulation software capabilities, and reporting standards, often aligning with international best practices like ASHRAE Standard 90.1 Appendices G or ASHRAE Standard 189.1[^10].

Troubleshooting

- Input Data Errors: Incorrect geometry, material properties, schedules, or HVAC inputs are common sources of error. Double-check all inputs meticulously.

- Modeling Complex Systems: Accurately modeling complex HVAC systems, controls, or natural ventilation interactions can be challenging. Consult software documentation, tutorials, or seek expert advice.

- Convergence Issues: Simulations may fail to converge if the model is unstable or contains errors. Check error messages and refine the model geometry or system definitions.

- Interpreting Results: Simulation outputs can be extensive. Focus on key metrics (EUI, peak loads, comfort hours) and understand what they mean in the context of the project goals and the tropical climate. Don’t treat the simulation results as absolute truth, but rather as indicative predictions based on assumptions.

- Software Limitations: Be aware of the capabilities and limitations of your chosen BPS software, especially regarding modeling specific passive strategies, humidity, or complex control sequences.

By following these practical guidelines and applying BPS thoughtfully, practitioners in Vietnam can design and assess buildings that not only meet current energy efficiency standards but also contribute to decarbonization goals and are resilient to the inevitable impacts of climate change. This is vital for Vietnam’s sustainable development and the well-being of its population.

References

Related Content