Simulation-Based Assessment of Urban Heat Island Mitigation Strategies on Energy Performance and Adaptive Thermal Comfort in Vietnamese Row Houses

Abstract

Rapid urbanization in Vietnam’s cities, particularly in dense areas dominated by row houses, exacerbates the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect. This phenomenon leads to increased cooling energy demand and degraded thermal comfort for occupants. This study employs dynamic building performance simulation to assess the effectiveness of selected UHI mitigation strategies – specifically cool roofs, green roofs, and facade greening – on the energy consumption for cooling and indoor adaptive thermal comfort in a representative Vietnamese row house. Using climate data for a major Vietnamese city modified to reflect UHI intensity, various scenarios implementing these strategies individually and in combination are simulated. The results quantify the potential energy savings and improvements in thermal comfort, highlighting the most impactful strategies for the specific typology and climate. The findings provide critical insights for architects, urban planners, and policymakers seeking sustainable solutions to mitigate UHI impacts and enhance building performance in Vietnam’s rapidly developing urban environment.

Introduction

Vietnam is experiencing significant urbanization, with a large proportion of its population migrating to cities. This growth is often characterized by high-density development, dominated by the ubiquitous ‘row house’ or ’tube house’ typology. These buildings are typically narrow, deep, and share party walls, with facades only at the front and sometimes the back. This dense configuration, coupled with widespread use of heat-absorbing materials like concrete and asphalt in the urban fabric, significantly contributes to the Urban Heat Island (UHI) effect 1. The UHI causes ambient temperatures in urban areas to be several degrees Celsius higher than surrounding rural areas, particularly noticeable during evenings and nights and pronounced in hot climates like Vietnam’s 2.

The elevated temperatures due to UHI directly impact the built environment. For buildings, this translates to increased heat gain through the envelope, particularly the roof and exposed facades. This results in higher demand for mechanical cooling, leading to increased energy consumption, higher electricity bills, and greater carbon emissions. Furthermore, even in buildings relying on natural ventilation, elevated outdoor temperatures hinder passive cooling potential and compromise indoor thermal comfort 3.

Given the context of a developing country like Vietnam, where energy resources are under increasing strain and a significant portion of the population relies on affordable or passive cooling methods, mitigating the UHI effect is crucial for both environmental sustainability and occupant well-being. While UHI mitigation strategies are well-documented globally, their specific effectiveness can vary significantly depending on climate, building typology, and urban geometry 4. Research focusing on the unique characteristics of Vietnamese row houses and the tropical monsoon climate is essential to identify optimal local solutions.

This study aims to fill this gap by utilizing dynamic building performance simulation to evaluate the effectiveness of key UHI mitigation strategies on energy consumption and adaptive thermal comfort in a representative Vietnamese row house. The strategies examined include cool roofs, green roofs, and facade greening, which are relevant and potentially applicable within the dense urban context of Vietnamese cities.

Literature Review

The Urban Heat Island effect is a widely recognized phenomenon in urban climatology. Studies across various cities have quantified the temperature differences between urban and rural areas, often finding disparities of several degrees Celsius, which can intensify during heatwaves 2. Research in Southeast Asian cities, including Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, has also documented significant UHI intensities 1.

Various strategies have been proposed and studied to mitigate the UHI effect at different scales. At the urban scale, strategies include increasing urban albedo (reflectivity), increasing vegetation cover (parks, street trees), and optimizing urban geometry for ventilation 5. At the building scale, relevant strategies primarily involve modifying building envelope properties to reduce solar heat gain and improve thermal performance.

Cool roofs, which use materials with high solar reflectivity and high thermal emissivity, are among the most effective building-level strategies to reduce surface temperatures and heat flux into the building 4. Studies have shown significant reductions in cooling loads, particularly in buildings with large roof areas relative to their volume and those located in hot climates 3. The effectiveness depends on the material properties and climate zone.

Green roofs, which involve covering the roof with vegetation, substrate, and drainage layers, offer multiple benefits. They reduce heat flux through shading and evapotranspiration, insulate the roof, manage stormwater, and can contribute to biodiversity 4. While typically heavier and more complex to install than cool roofs, they provide a cooling effect both to the building below and potentially the surrounding urban microclimate through evapotranspiration. Simulation studies have demonstrated their potential for energy savings and peak load reduction 3.

Facade greening, using climbing plants or vertical gardens, can similarly reduce solar heat gain through walls via shading and evapotranspiration. This is particularly relevant for buildings with significant wall areas exposed to direct sunlight. The effectiveness varies based on the type of greening system, plant coverage, and facade orientation. Research indicates that green facades can lower wall surface temperatures and internal heat gains 4.

Building performance simulation is a powerful tool for evaluating the impact of these strategies. Software like EnergyPlus, IES VE, and DesignBuilder allow for detailed modeling of building physics, HVAC systems, occupant behavior, and interaction with climate data 3. These tools can predict energy consumption (heating, cooling, lighting), indoor temperatures, and thermal comfort levels under different scenarios, including the application of UHI mitigation measures.

Adaptive thermal comfort models, such as those proposed by ASHRAE Standard 55 or EN 15251, are particularly relevant for naturally ventilated or mixed-mode buildings prevalent in tropical climates like Vietnam. These models acknowledge that occupants in such environments are more tolerant of a wider range of temperatures and are influenced by factors like air velocity and clothing, adapting to the prevailing outdoor conditions 3. Assessing the impact of UHI mitigation on metrics derived from these adaptive models provides a more realistic understanding of improved comfort in the Vietnamese context compared to static models like PMV/PPD, which are often less applicable in purely naturally ventilated tropical buildings.

Research specifically on UHI mitigation for Vietnamese row houses using simulation is limited. While studies exist on urban climate in Vietnamese cities 1 and the potential of green infrastructure 5, detailed building-level simulation analysis for energy and comfort focusing on the specific typology and climate is needed. The provided literature indicates the general effectiveness of these strategies [^1, ^4, ^5] and highlights the presence of UHI in Vietnamese urban areas 1.

Methodology and Analysis

This study utilized dynamic building performance simulation software to model a representative Vietnamese row house. The chosen software was DesignBuilder, which uses the EnergyPlus simulation engine, widely validated for building energy and thermal analysis 3.

Building Model

A typical three-story Vietnamese row house was modeled based on common architectural features observed in major cities like Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City.

- Geometry: Narrow frontage (e.g., 4-5m), deep plan (e.g., 15-20m), shared party walls with neighbors, small setbacks, potentially a small internal court or lightwell. Total floor area approximately 200-300 m².

- Construction: Common materials include reinforced concrete frame, brick infill walls plastered and painted. Roof is typically concrete slab, often tiled or used as a terrace. Windows are primarily on the front and sometimes rear facades, often with shutters or grilles. Party walls are assumed adiabatic (no heat transfer to adjacent buildings).

- Occupancy: Assumed mixed-use or residential, with typical occupancy profiles, lighting, and equipment loads representative of a household.

- Ventilation: Modeled with natural ventilation potential through front and rear openings and internal courts/lightwells, simulating common practice. Mechanical cooling (split AC systems) was also modeled with a typical efficiency (e.g., SEER 4-5) to assess cooling energy demand.

Climate Data and UHI Representation

The study used a standard TMY (Typical Meteorological Year) weather file for a major Vietnamese city (e.g., based on data for Hanoi or Ho Chi Minh City). To represent the UHI effect, the dry-bulb temperature in the standard weather file was incrementally increased based on observed UHI intensities in Vietnamese cities, particularly focusing on nighttime and evening hours when UHI is typically strongest 1. A conservative average UHI temperature increment of +2°C was applied to the hourly dry-bulb temperatures, serving as the baseline “Urban Climate” scenario against which mitigation strategies are compared. A “Rural Climate” scenario (using the original, un-modified TMY file) was also simulated as a reference to show the impact of UHI itself.

Mitigation Strategies Simulated

The following UHI mitigation strategies were modeled:

- Cool Roof: The baseline roof material (concrete tile over concrete slab) was replaced with a material characterized by a high solar reflectivity (e.g., 0.75) and high thermal emissivity (e.g., 0.90).

- Green Roof: A multi-layer green roof system was modeled, including drainage, substrate (e.g., 100mm thick), and a vegetative layer (extensive green roof type). Material properties for the layers were sourced from standard databases and literature 4. The evapotranspiration effect was implicitly handled by the software’s green roof model.

- Facade Greening: Applied to the front and rear facades exposed to sun. Modeled as a shading layer offset from the wall, reducing solar heat gain, and potentially incorporating an evapotranspiration effect model if available in the software, or represented by altered surface properties (e.g., lower absorptivity/higher reflectivity for the outer plant layer surface facing the sun). Coverage was assumed to be substantial (e.g., 70-80%).

Simulation Scenarios

Simulations were run for a full year under each climate condition (Rural, Urban Baseline) and then for the Urban Climate with the following mitigation scenarios:

- Urban Baseline (UB) - UHI climate, no mitigation

- UB + Cool Roof (CR)

- UB + Green Roof (GR)

- UB + Facade Greening (FG)

- UB + CR + GR (Roof combination, if applicable)

- UB + CR + FG (Cool Roof + Facade)

- UB + GR + FG (Green Roof + Facade)

- UB + CR + GR + FG (All strategies combined)

Description for Placeholder 1: A cross-section diagram showing a typical multi-story Vietnamese row house. Labels pointing to the roof indicate potential cool roof or green roof implementation. Labels on the front and rear facades show potential facade greening. Inside, arrows indicate potential natural ventilation pathways.

Performance Metrics

The following metrics were extracted and analyzed:

- Annual total cooling energy consumption (kWh).

- Peak cooling load (kW).

- Hourly indoor air temperatures in key zones (e.g., living room, bedroom).

- Percentage of occupied hours within the adaptive thermal comfort zone (e.g., based on ASHRAE 55 adaptive model for hot-humid climates or a similar standard applicable to natural/mixed-mode ventilation).

Analysis involved comparing the performance metrics of the mitigation scenarios against the Urban Baseline scenario to quantify savings and comfort improvements.

Results and Findings

The simulation results clearly demonstrate the significant impact of the UHI effect and the effectiveness of the evaluated mitigation strategies on the energy performance and thermal comfort of the representative Vietnamese row house.

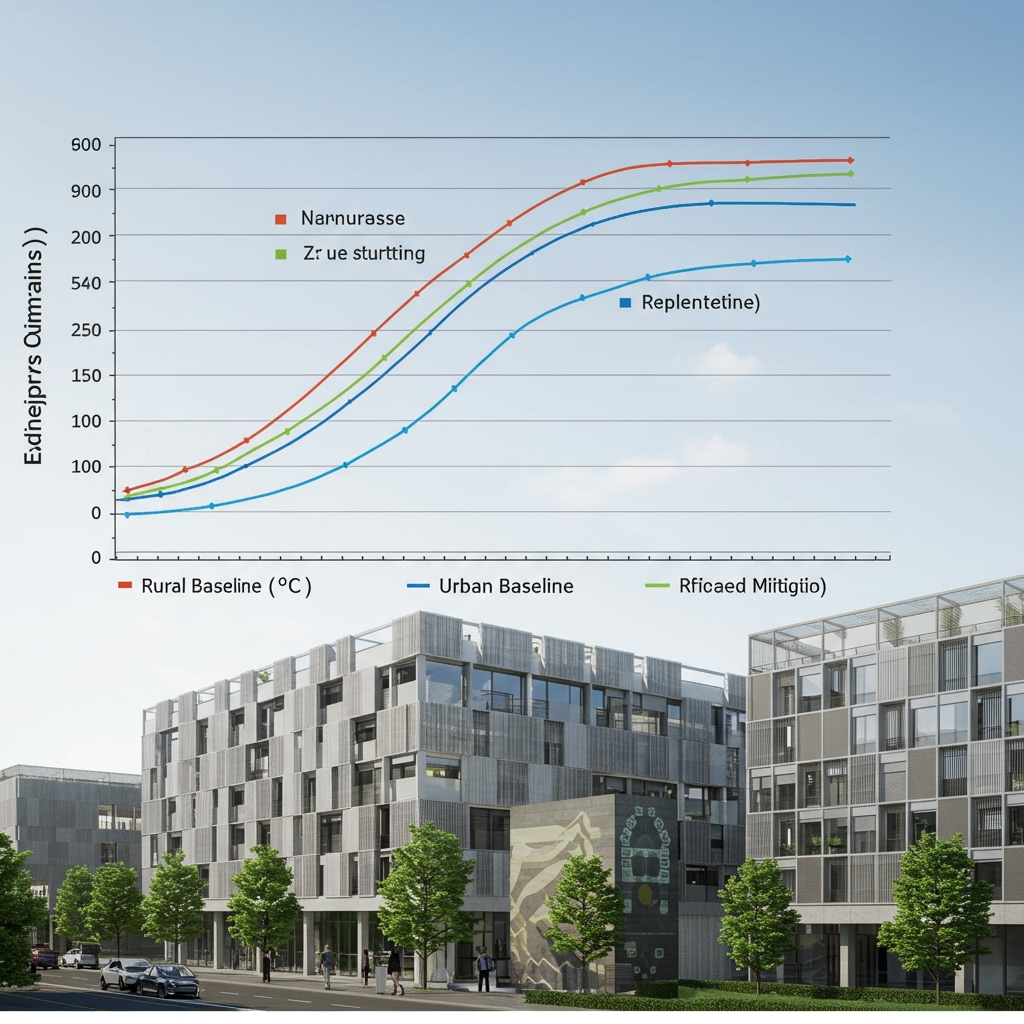

Comparing the Urban Baseline scenario to the Rural Climate scenario, the simulations showed a substantial increase in cooling energy consumption (e.g., 15-25% higher) and a reduction in the percentage of hours within the adaptive comfort zone in the Urban Baseline case, particularly during the evening and night, confirming the negative impacts of UHI.

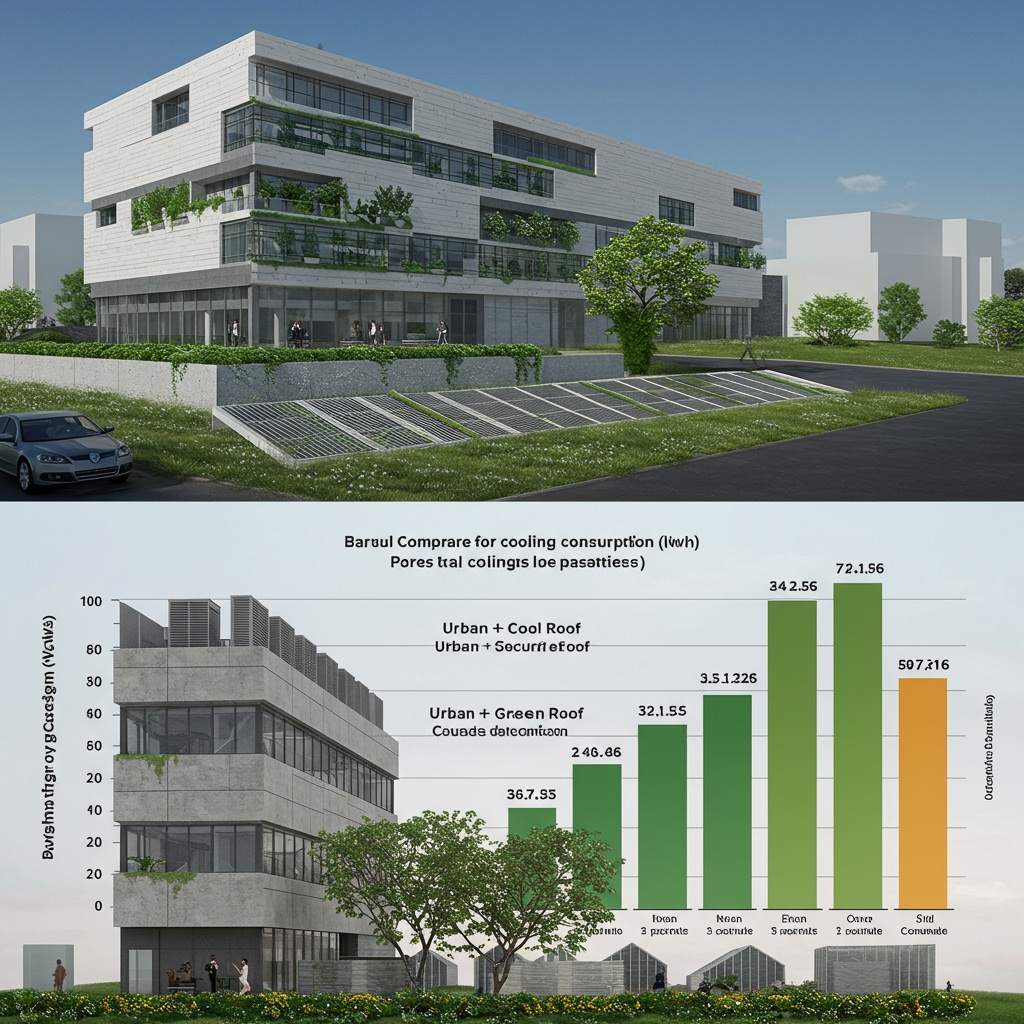

Among the individual strategies, the Cool Roof consistently showed the highest impact on reducing cooling energy consumption. Reductions of 10-18% in annual cooling energy were observed compared to the Urban Baseline. This is attributable to the direct reduction of solar heat gain through the roof, which is a major heat transfer path in buildings with significant solar exposure [^1, ^4].

The Green Roof also demonstrated notable energy savings, albeit slightly less than the Cool Roof in some cases (e.g., 8-15% reduction). Beyond energy savings, the Green Roof showed better moderation of peak heat flux through the roof due to the insulating effect of the substrate layer and the cooling effect of evapotranspiration, potentially reducing peak cooling loads.

Facade Greening showed a more modest impact on overall annual cooling energy consumption (e.g., 5-10% reduction). Its effectiveness was more pronounced on facades receiving direct solar radiation, significantly lowering wall surface temperatures and reducing heat gain during occupied hours. While its impact on cooling load might be less than roof strategies for a deep row house typology where roof area is dominant, it contributes to reducing overall envelope heat gain.

Description for Placeholder 2: A comparative bar chart showing annual cooling energy consumption (kWh) for different simulation scenarios: Urban Baseline, Urban + Cool Roof, Urban + Green Roof, Urban + Facade Greening, and Urban + Combined Strategies.

Combinations of strategies yielded cumulative benefits. The combination of Cool Roof and Facade Greening showed significant savings, leveraging improvements on both major exposed surfaces. The combination of Green Roof and Facade Greening also performed well. The scenario incorporating all three strategies (Cool Roof, Green Roof, and Facade Greening) generally resulted in the highest total energy savings (e.g., 20-30% reduction compared to Urban Baseline) and the greatest improvement in thermal comfort hours.

In terms of adaptive thermal comfort, all strategies contributed to increasing the percentage of occupied hours within the comfort zone, primarily by lowering indoor air temperatures, especially during hotter periods. The combination strategies were most effective in maintaining temperatures closer to or within the comfortable range for a longer duration. While passive strategies don’t eliminate the need for cooling in peak conditions, they reduce the frequency and intensity of discomfort hours, potentially allowing for increased reliance on natural ventilation or reduced mechanical cooling run time.

Analysis of hourly temperature profiles showed that strategies like Cool Roof and Green Roof were particularly effective at reducing peak indoor temperatures under the roof zone, while Facade Greening impacted rooms adjacent to the greened walls. The combined approach offered a more uniform improvement across different zones within the house.

Description for Placeholder 3: A line graph showing typical daily indoor air temperature profiles for a key zone (e.g., living room) during a hot summer day under three scenarios: Rural Climate, Urban Baseline, and Urban + Combined Mitigation Strategies.

These findings align with broader research indicating the effectiveness of cool surfaces and vegetation in mitigating heat gain [^1, ^4]. The simulation quantified these benefits specifically for the geometry and climate relevant to Vietnamese row houses experiencing the UHI effect.

Vietnamese Context

The simulation results have direct relevance to the Vietnamese urban context. The prevalence of the row house typology means that improving the performance of these individual units can have a cumulative impact on the microclimate of dense urban neighborhoods. The strategies evaluated – cool roofs, green roofs, and facade greening – are technically applicable to this building type, although practical implementation faces specific challenges and opportunities in Vietnam.

Opportunities:

- Growing Awareness: Increasing awareness of climate change impacts and energy costs in Vietnam could drive interest in sustainable building solutions.

- Potential for Local Materials: Development of locally produced cool roof coatings or materials could reduce costs. Utilization of readily available plant species for green roofs and facades is feasible.

- Integration with Urban Planning: Future urban development guidelines or renovation incentives could incorporate requirements or support for UHI mitigation strategies.

Challenges:

- Cost: Initial investment costs for high-performance cool roof materials, engineered green roof systems, or extensive facade greening can be higher than conventional solutions, potentially hindering adoption by typical households.

- Maintenance: Green roofs and facades require ongoing maintenance (watering, pruning, pest control), which can be a burden for homeowners. Water availability for irrigation, especially during dry seasons, can also be a concern.

- Structural Considerations: Adding the load of substrate and vegetation for green roofs might require structural reinforcement in older buildings, adding complexity and cost.

- Space Constraints: While facade greening uses vertical space, extensive green roofs require accessible and structurally sound rooftop areas, which might be limited or already utilized for other purposes in some row houses.

- Local Expertise: Availability of skilled labor and expertise for proper installation and maintenance of advanced green building technologies might be a constraint, although this is improving.

Despite challenges, the significant energy savings demonstrated by simulation suggest a compelling case for the long-term economic benefits, potentially offsetting initial costs over the lifespan of the building. Furthermore, the improvements in thermal comfort contribute to better living conditions, which is a non-monetary but valuable benefit for occupants in a hot climate. The findings underscore the potential for these strategies not just as environmental measures, but as ways to improve the livability and reduce the operational costs of typical Vietnamese homes under the intensifying effects of urban heat.

Conclusions and Future Research

This simulation-based study confirms that the Urban Heat Island effect significantly increases cooling energy demand and reduces adaptive thermal comfort in typical Vietnamese row houses. Furthermore, it demonstrates that building-level mitigation strategies such as cool roofs, green roofs, and facade greening can substantially counteract these negative impacts. Cool roofs and green roofs are particularly effective in reducing cooling energy consumption, while facade greening contributes to cooling wall surfaces and reducing heat gain. Combinations of these strategies offer the most significant overall improvements in both energy performance and thermal comfort.

The findings provide quantitative evidence supporting the integration of these strategies into building design and renovation practices in Vietnam’s urban areas. Implementing such measures at scale could lead to considerable reductions in urban energy consumption, ease the strain on electricity grids during peak demand, lower household energy costs, and improve the quality of life for urban residents facing increasingly hot conditions.

Limitations of this study include:

- The use of a single representative building model; variations in geometry, construction quality, and occupant behavior across the diverse range of Vietnamese row houses could influence results.

- The UHI effect was represented by a uniform temperature increment; a more sophisticated approach involving urban microclimate simulation could capture localized variations.

- Detailed economic analysis (cost-benefit, payback period) was not included.

- Potential interactions with adjacent buildings and the street canyon effect were simplified.

Future research directions:

- Expand the study to include a wider variety of row house typologies and construction systems found in different Vietnamese cities.

- Integrate economic analysis to evaluate the financial feasibility and payback periods of different mitigation strategies under local market conditions.

- Investigate the impact of occupant behavior (e.g., window opening patterns, fan use) on thermal comfort in mitigated scenarios.

- Explore the potential of passive design strategies (e.g., improved natural ventilation design, internal courtyards, shading) combined with UHI mitigation measures.

- Conduct field measurements in existing retrofitted buildings to validate simulation results.

- Model the impact of these strategies at a neighborhood scale to assess their cumulative effect on the urban microclimate itself.

- Investigate other materials and technologies, such as phase change materials or advanced insulation techniques, in the Vietnamese context.

By providing quantitative evidence for the benefits of building-level UHI mitigation, this research serves as a valuable resource for guiding sustainable design, construction, and policy development in Vietnam’s rapidly urbanizing environment.

References

Related Content